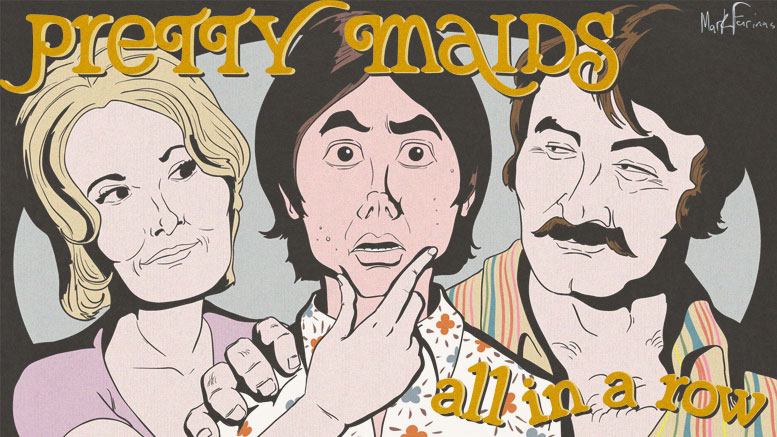

Welcome back to our series on Gene Roddenberry’s work between Star Trek incarnations. Last time we looked at the gender bending antics of Planet Earth. In this entry we try very hard to look away from the train wreck that is Pretty Maids All in a Row.

Sometimes we leave the best for last. Sometimes we avoid things because we just don’t want to deal with them until we have to. This review of the 1971 feature film Pretty Maids All in a Row, which is actually the first production Gene Roddenberry was involved with after Star Trek’s cancellation, is more of the latter. But, there is a point to saving Pretty Maids for last beyond mere procrastination. After all, this is the film that most influenced all of Gene’s work going forward. That’s a big leap, I know. And it’s one you, the reader, would never have even considered if we hadn’t looked at all his other forgotten works first.

Pretty Maids All in a Row is, at its heart, a “sex comedy”, though I find it does neither of those descriptors justice. Because of its strong sexual nature it is nearly impossible to talk about in-depth without being somewhat graphic. Therefore, the more pearl-clutching amongst you might want to turn back. You’ve been warned.

The story of Pretty Maid’s production is filled with Star Trek participants from both in front of and behind the camera. Herb Solow, an executive at Desilu who helped produce Star Trek’s first two seasons, had just started a short tenure as a Vice President at MGM. At the studio’s behest, Herb was looking for an edgy, X-rated story that could win as many Oscars as Midnight Cowboy. How he thought Pretty Maids was their best shot is a complete mystery to me. After passing on the first script adaptation, Herb needed someone to get this smut on screen. Having witnessed Roddenberry’s lecherous and lascivious personal behavior first hand, Solow probably thought Gene was the best man to adapt a story about a teacher who seduces and murders his female students.

I started my preparation for this review not by rewatching the film, but by searching for and procuring a copy of the 1968 Francis Pollini book it’s based on. This was not easy. The book has been out of print for ages and no used bookstore in my area had a copy. Neither the book nor Pollini even have a Wikipedia entry. What’s worse, when shopkeepers looked up the title and saw its creeptastic cover containing an older man gently lifting the shirt of a clearly underage girl I had to explain exactly why I’d want such a thing. “You know Gene Roddenberry? Yeah, the Star Trek guy. He wrote and produced the film version of this. I know, gross.”

The book starts out with Ponce, a sexually frustrated high school student, rushing into the bathroom to relieve his lustful urges after ogling his teacher during class. This is when he stumbles upon a dead girl, face down in the toilet with her bare tokhes sticking up in the air. Pollini then spends a full four and a half densely-worded pages describing how nubile the corpse still is and how conflicted Ponce feels over whether or not he should sexually molest it. At this point I yawned so hard my eyes rolled too far back into my skull to continue reading the book, and I haven’t picked it up again for more than a referential skim since.

The film itself starts off similarly, but with the opening credit sequence following Ponce on his scooter as he rides to school. Once he gets to the bathroom and finds the prone body he does momentarily reach for her rear, but as soon as it’s obvious she’s dead he at least makes a run for help. The sexualization of female-focused violence is pretty common in today’s media, whether it’s “edgy” cable TV shows, horror films, or video games, but even by 1971 it had become more banal than shocking. Roger Ebert, who panned Pretty Maids in his review of it, had only one year earlier written the film Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, in which a woman fellates a gun before it blows her head off. Dirty Harry, which came out the same year as Pretty Maids, features a nude woman’s long dead body being pulled slowly out of a hole in the ground. She isn’t blue or rotting or stiff, but rather as pink and supple as a living thing. Even the 1968 sci-fi soft porn film Barbarella, written by Pretty Maids’ director, Roger Vadim, features Jane Fonda getting bitten and pecked bloody while wearing barely-there space suits. My stars! An uptick in sexual violence against women in film at the height of second-wave feminism? What could that possibly mean?

There’s no point in writing a complete synopsis of this film as I’ve done in my other reviews because nothing really happens in it. It’s a pretty dull detective procedural intermixed with classic high school film antics and bizarre sexual hijinks that only people too young to be admitted into the theater would find funny. The film’s themes are better addressed through its characters than its narrative, so I’ve taken that approach instead.

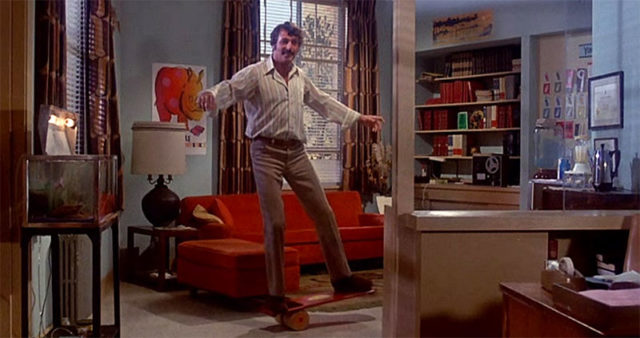

High school counselor and teacher Mike “Tiger” McDrew, played by multiple Golden Globe Award winner Rock Hudson, is the alpha and the omega character of the film. You can’t talk about other characters without addressing him first, but you can’t fully understand him without discussing the many people he’s caught in his intricate web. Simply put, McDrew is a middle-aged sex fiend who beds the most nubile of his female students during office hours and then kills them when they threaten to reveal the affair. Pretty Maids is billed as a “murder mystery,” but it’s clear ten minutes in that it’s McDrew who’s doing the killing.

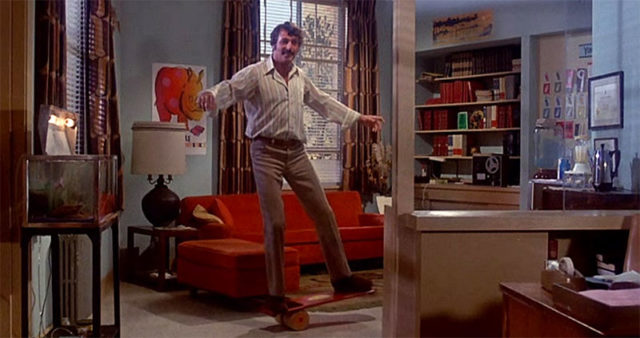

If anything positive can be said about McDrew, it’s that he’s a unique take on the serial killer character. He’s a sort of sexually charged, silverback gorilla of a man who proves his virility with feats of strength and organic smoothies all while wearing a mustache that would soon be synonymous with porn. He exudes a kind of old-fashioned, John Wayne-style manliness, but preaches new age ideas about a liberal future lead by wise and promiscuous young people. His students love him. They “reach,” as the space hippies in “The Way to Eden” would say. But McDrew is no Doc Sevrin. Sevrin was an obvious madman. McDrew never really says anything an enlightened audience could disagree with. Of course the children are our future. Of course everyone should be free to follow their passions without shame, sexual or otherwise.

It’s also interesting to point out that McDrew is the coach of his school’s football team. It’s almost prescient how the faculty and community ignore and deny his barely concealed philandering and obvious guilt because he’s led the school through so many victories. At one point, the local sheriff catches McDrew schtupping one of his students in a parking lot and would rather discuss players and scores than address the naked, underage girl in his car. Jerry Sandusky couldn’t find a better analogue.

McDrew’s protégé is the aforementioned horn-dog, Ponce de Leon Harper, who found the first of McDrew’s victims rump-up in the lavatory. Ponce is an awkward, virginal “nice guy” who doesn’t understand why all the “jerks” have regular coitus while he continually strikes out. The film is seen mostly through his gaze, which is exceedingly male. As with most boys, Ponce has never been taught that women are fully formed human beings, so we mostly see the world as a long parade of cleavage and upskirts that can never be embraced and furiously dry-humped.

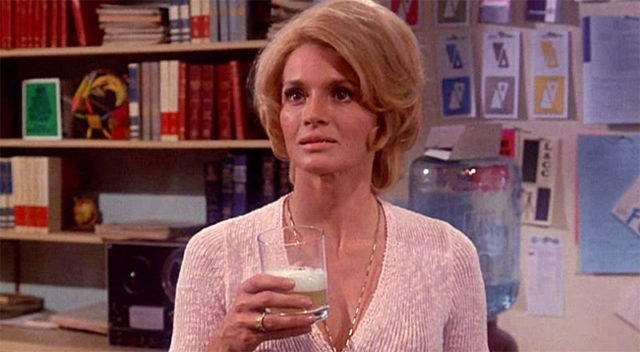

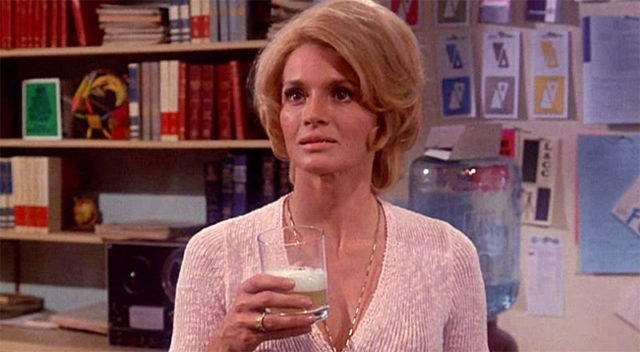

Ponce’s main object of desire is his braless, miniskirted teacher, Ms. Betty Smith, played by Saturn, Golden Globe, and Emmy winner Angie Dickinson. Like Ponce, her life is confusingly sexless. Any attempt at using her feminine wiles on the appropriately aged McDrew are met with well-practiced aloofness because he’s a walking pedobear prototype and she’s the embodiment of the “too old” meme. Knowing how hard up the two of them are and having no sense of right or wrong, McDrew convinces Ms. Smith to sexually mentor Ponce during some after-hours tutoring at her place. After several “accidental” intimate collisions, she applauds the boy’s erection as if he were a baby taking its first steps. Eventually the two give in to each other during a sponge bath necessitated by a horrible chocolate duck mishap.

Before he was Kojak, but after he was Charles Sievers, Emmy and Golden Globe-winning and Oscar-nominated Telly Savalas was Pretty Maids’ intrepid detective, Sam Surcher. Savalas is wry and delightful, but utterly wasted in this role that amounts to nothing more than killing time. Along with his deputies, played by James “Scotty” Doohan and William “Koloth” Campbell, Surcher just sort of muddles about as a straight man set up against the insanity of a high school more interested in the football score than the amount of bodies piling up. Doohan and Campbell fare even worse than Savalas, having almost no lines. Campbell, at least, has a mildly humorous scene where he carries the librarian through the corridors of the school to see how long it would have taken the killer to get the body into the bathroom. What this test gets them is beyond me since they don’t know where the girl was murdered in the first place.

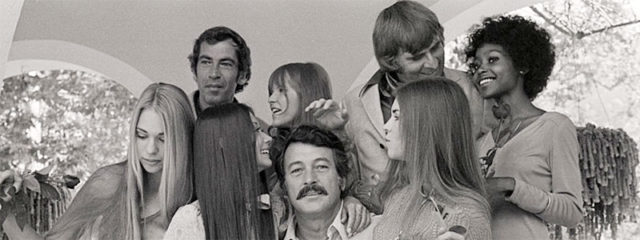

McDrew’s lovers/victims are the titular Pretty Maids, and they have very little to do as well except be naked and die. I will repeat again that this is a sex comedy, meaning the intention of the nudity is to titillate the audience. The film itself was dubiously marketed as having more skin in it than any mainstream production up to that point and its starlets promoted it with their own Playboy spreads. I’d also like to remind you that these girls are supposed to be between the ages of 15 and 17 years old. Pretty Maids relies on the bizarre trope that underage girls are somehow more sexually advanced than their male counterparts and, therefore, ripe for the picking. While Ponce is the epitome of a lanky, spotted youth, the Maids are graceful, well-groomed super models sporting barely-there outfits designed by Star Trek’s own William Ware Theiss.

Surcher’s biggest scenes are spent interrogating the Maids, who are a Roddenberry rainbow of ethnicities. The scantily clad children have some interesting ideas to share with the world-worn detective. One brazenly states, “If a boy didn’t make sexual advances toward me, I think that would be pretty unnatural.” This is presented as some kind of enlightened truth when it’s really just learned helplessness. As the only one who even remotely suspects McDrew as the killer, Surcher feels like he’s supposed be an intellectual foil for the wayward coach’s laissez-faire philosophy, but he just never gets there. Instead he listens and raises an eyebrow and moves on to the next crazy situation. Rinse. Repeat.

Even after McDrew’s apparent suicide, when Surcher spots Lady McDrew holding plane tickets to Brazil, he doesn’t make a move to stop her or head her off at the airport. We know McDrew’s on the run and Surcher is wise to him, but nothing comes of it. Makes you wonder who’s supposed to be the hero here. Chalk it up to “boys will be boys.”

I’ve talked about Roddenberry writing himself into his scripts before. Wesley Crusher is a confirmed example and Spectre’s Amos Hamilton is a pretty safe bet. I think Tiger McDrew is another. While not his own, original character, McDrew is very similar to Roddenberry as far as his sexual proclivities go. According to Herb Solow’s “Inside Star Trek,” Gene often bragged about “late night casting meetings” with various actresses. In the same book, Penny Unger, Gene’s secretary during The Original Series, reports making out with him once. Nichelle Nichols and Majel Barrett were both cast in Gene’s 1963 show, The Lieutenant, before beginning long-term, concurrent affairs with him. As we know, Barrett later married Gene in 1969. Susan Sackett, Gene’s assistant from 1974 until his death in 1991, claims to have carried on an affair with him after being aggressively pursued. Basically, every alleged intimate relationship that Gene Roddenberry had after becoming a television producer was with an underling.

Obviously Gene did not fool around with anyone under consenting age, but the power imbalance between an actress and a producer or a secretary and an employer is eerily similar to that of a student and a teacher. In every one of those cases authority has a problematic influence on the relationship’s outcome.

Roddenberry’s kinship with the McDrew character becomes even more apparent in the scenes where Tiger gives his students utopian lectures of the kind that would sound familiar to anyone who’s heard Gene give an interview. I mentioned at the beginning of this review that Pretty Maids is a major turning point and influence on Gene’s work. It’s the moment when he realizes he can write his zany, lopsided ideas on free love right into his scripts and someone will actually pay him for it.

The original Star Trek was a sexy show, no doubt. While there was way more female skin, revealing male outfits were not lacking. Kirk himself spent half the first season with his shirt off for one reason or another. But that act of sex itself was either unattainable due to professional commitments, or used as a bargaining chip to convince enemies to lower their guard. No one was defined by their sexuality, nor did they celebrate it. There’s lots of screwing going on, but no one really enjoys it.

Comedy was also a no-no on The Original Series, the first season of which is remarkably grim. Some specifically comedic episodes show up in the second season, including “The Trouble With Tribbles” and “A Piece of the Action.” This kind of hilarity, as well as the inappropriate bridge jokes that would often end episodes that year, were the work of line producer Gene Coon. This brought him to blows with Roddenberry who wanted the series played straight. Though he still contributed storylines well into the third season, Coon was dropped from his production duties because of this rift.

These attitudes toward sex and comedy change after Pretty Maids. Gene’s first original television production after Star Trek, Genesis II, features a society called Tyrania whose main selling point is its sensual liberties. This includes a device called a “stim” that can induce extreme pleasure. If it hadn’t been for the slavery, hero Dylan Hunt would have preferred living in Tyrania with it’s twin belly-buttoned seductresses instead of with his sensually subdued PAX saviors. Even the method of the Hunt’s rebirth is sexual in nature. Years later, in Gene’s horror mystery Spectre, we witness another evil sect reveling in orgies, its leader vocally unashamed of bucking his family’s prudish mores. Spectre, Planet Earth, and The Questor Tapes (the last co-written by Gene Coon of all people) may not be terribly funny or sexy, but they try pretty hard to be both.

The Motion Picture is Gene’s first attempt at inserting his sexual politics into Star Trek with the alien race known as the Deltans. Initially created for the scrapped television sequel, Star Trek II, the Deltans were described in the writer’s guide as having sex during every social interaction, sort of like bonobos. So strong was their drive and so great was their skill that Deltans had to take an oath of celibacy before serving on a Starfleet vessel. When Star Trek: The Next Generation was conceived, Betazoids replaced Deltans as the sultry Greek letter aliens du jour. Possessing almost all of the same social characteristics and abilities of Deltans, Betazoids upped the ante by requiring nudity at important social events, such as weddings. Their women were also supposed to have four breasts each, but Dorothy Fontana put the kibosh on that one. Both races would continually roll their eyes at humanity’s perceived sexual immaturity.

The novelization of The Motion Picture, written by the Great Bird himself, gets even more raunchy with Gene actually addressing (and refuting) Kirk/Spock slash fiction. At the same time he makes their relationship so intense that it seems weird that they’re not having sex (look up “T’hy’la” some time). There are regular status reports on the state of Kirk’s genitals, with the good captain getting a chubby in a meeting with his ex-wife and upon seeing his new Deltan navigator for the first time. Spock describes the Enterprise as having private rooms where he overhears couples boinking. Decker actually bones the Ilia-probe with V’Ger listening in. And, of course, there’s so much more discussion of Deltan promiscuity. And what the heck was Kirk’s mom doing with a “love instructor”? That one is mentioned on page one!

Sex comedy elements invaded many of Next Generation’s first season episodes. “The Naked Now” replaced the personality-specific drunkeness of its Original Series inspiration with blanketed ship-wide horniness. In “Justice” the planet Rubicun III is infested with bushy blonde people who literally run around in white fetish gear and greet everyone with lingering hugs. Do I even need to mention Wesley’s dick joke? Riker, who was supposed to be as much Jim Kirk as Will Decker, is far more outwardly sensual than either of his inspirations. He spends his time watching holograms of comely young women playing elevator music and openly offers to share his computer-generated love doll with Picard in “11001001.” This not only acknowledges that the holodeck is used for nookie, but that everyone’s okay with it. In “Code of Honor,” “Haven,” and “Angel One,” crew members express their attraction toward guest stars without shame or reservation. This is not your grandpa’s Star Trek, but it’s definitely Gene’s.

For a project Gene was accidentally thrown into, Pretty Maids All in a Row sure did have a lasting impact on his work. It’s hard to tell whether the experience unleashed his already established beliefs on sexuality or made him invent new ones to help legitimize his womanizing lifestyle. After all, people were already lauding his thoughts on technology, race relations, and pacifism. Why wouldn’t they want his thoughts on sex, too? No matter which way it happened, it certainly turned Star Trek into a world filled with randy aliens, even randier crew members, and “love instructors.” Tiger McDrew would definitely approve of that last one.

Random Facts:

- This is the only post-Star Trek Roddenberry production to not have Majel Barrett in it somewhere as an extra.

- Gene did, however, get his daughter, Dawn, cast as “Girl #1.” She also appeared as an Onlie in The Original Series episode, “Miri.” I reached out to Roddenberry family members hoping they could identify her, but never heard back. Since only speaking parts get credited, I’m assuming she’s the blonde student at the 3:30 mark who says, “Dig that figure” in reference to Angie Dickinson’s jiggling caboose.

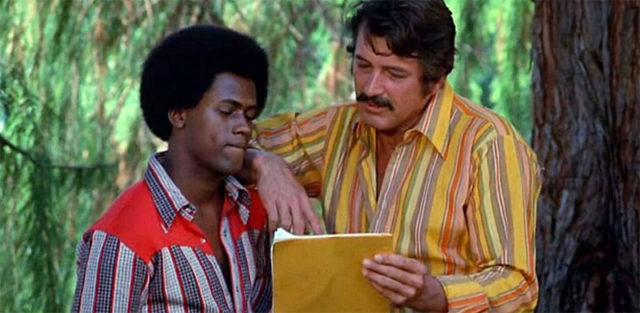

- In the vein of Roddenberry’s socially conscious messaging, one legitimately funny, and sadly still relevant, scene in the film that’s definitely not in the book features the town sheriff grabbing a random black student and accusing him of being the murderer before even looking at the scene or talking to witnesses.

- Golden Globe and Emmy award-nominated and Saturn-winning Roddy McDowell plays the constantly flustered school principal, as if there wasn’t too much wasted talent in this film already.

- The opening theme song, “Chilly Winds,” was performed by the Osmonds. Kind of splatters a big ball of mud all over their squeaky-clean image.

- John David Carson, who played Ponce, cut his sci-fi teeth as the voice of Hanna Barbera’s “Dino Boy.” He later starred with Joan “Edith Keeler” Collins in a C-grade adaptation of H.G. Wells’ Empire of the Ants.

- The film’s hippie-dippie title font is like Gene’s daughter: unidentifiable, despite my best efforts. It may have been made just for the movie.

Mark’s other entries in the “Forgotten Roddenberry” series are well worth checking out. Click on to read about The Great Bird’s other 70’s exploits: Genesis II, Spectre, The Questor Tapes, and Planet Earth.

Nice job with such little to work with lol

I’m no prude, but after reading this….where’s the disinfectant?

It’s stuff like this that makes me laugh when fan’s attack any new Trek as being inconsistent with “Gene’s Vision.” That Trek shouldn’t (and wouldn’t under Gene) ever have “Game of Thrones” level sex, violence or adult themes.

Gene was no visionary. He was a run-of-the-mill hippie who had who happened to get work in Hollywood, and just lucked upon a cultural phenomenon.

I know you are trolling but BS. That’s like saying the Beatles weren’t visionary they were just a run of the mill pop/rock band because they were the first to do it.

Beatles weren’t the first, Beatles just were the first to succeed with that particular stylet.

Same thing with Trek.

Call it as you see it, but I’ve never felt like he was any kind of visionary. I adore what he created, but a lot of it was luck– particularly considering that it didn’t even initially succeed. Trek really took off when it was put in the hands of other people (like Nick Meyer, and Michael Piller).

The Beatles had genuine talent beyond their peers. But much of their fame and success came because they struck at the right place and right time. But I’m not sure I’d label them visionaries either. I think that word is thrown around a bit too much. I mean, everyone has a vision.

In both cases though, they were incredibly hard-working (Gene, and the Beatles). This quality is important, and definitely a factor in both successes. I mean, if Gene was a true visionary, why was only one thing he created ever a success?

A true visionary can repeat that success. See Stan Lee, Steve Jobs, or someone who sees the world so incredibly different than anyone else, like Ghandi, or Lincoln.

Gene was not alone in his vision of the future, he just happened to be the one working in Hollywood and an avenue to express it in fiction. You could say he was a science fiction visionary, I suppose.

I really think most of what you’re saying is unfair. Being a one hit wonder doesn’t exclude you from being a genius. That’s more hits than most. But Gene doesn’t have just one hit. TNG was a success because of the characters he created. No Star Trek incarnation since has had that level of popularity. Genesis II had really high ratings and is a pretty good pilot, but circumstances screwed it. Questor was also quite good, but was shelved due to executive meddling. Spectre is the flipping X-files 20 years too early. The pilot sucked, but the concept and lead characters were solid.

So Gene was not a one hit wonder in any sense of the word.

I try avoid using words like “genius” unironically. It’s way too easy to cite a person who worked hard, was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, and call them a genius for having done something big.

TOS didn’t become much of a hit until mid-70s syndication. TNG was a success, as Torchwood said elsewhere, largely because its name-recognition allowed it to survive long enough for better producers to take control of it away from GR. For the purposes of Roddenberry’s career achievements, we can validly name Star Trek as his single, albeit enormous success.

Regardless of what you or I think of any of them, none of Gene’s other pilots became popular properties in any significantly measurable way. Coulda/shoulda/woulda doesn’t count as a success.

While I disagree with Torchwood’s “run-of-the-mill hippie” exaggeration, most of his/her other points here are valid. GR likely never got over the fact that Star Trek was his only big thing.

By that metric, one could say post-Gene Trek series were riding on name recognition as they had a pretty consistent drop in ratings with only the most hardcore fans sticking through them. While DS9’s pilot is the highest rated individual episode ever, nothing else ever matched TNG’s first year as far as viewership. A massive audience of 9 million people doesn’t stick around and even grow for a bad show with a good name.

Roddenberry had different aspects of his personality. I saw him speak in the early ’80s and his vision was definitely on display — anticipating the rapid progress of bioscience for instance. Meanwhile he clearly was reveling in the sexual liberation of the ’60s and ’70s, and also found stimulation in his authority, perhaps inappropriately.

I feel comfortable accepting that he was something of a lech while also appreciating the good that he contributed. Just like I feel comfortable appreciating his vision for TOS while knowing that that same vision nearly condemned TNG to pablum.

I don’t believe it’s fair to label somebody a “lech” because they have a sexual attraction to women. It’s just a derogatory term meant to undermine a person. Strange how certain derogatory terms can become practically outlawed, but others get thrown so easily. They all serve the exact same purpose.

Basically any normal heterosexual man could be called a “lech” as they have the same strong sexual attraction to women. Evolution put that in to ensure we would mate and produce offspring so we could all be here today. Perhaps someday discussion about these things can reach a more intelligent level in the US where there is a definite lack of sophistication towards most things relating to sex. We may know we’ve reached that level when people stop calling people names like a bunch of 10 year olds.

When you look at his body of work, if you factor out Trek, what you are basically left with is a producer of soft core p0rn. GR was a product of his time, and he caught lightening in the bottle with Trek. Had he happened along three years later, he would have never wrestled the title of visionary away from Norman Lear. His body of work speaks more to the Civil Rights movement of the era, while Trek is remembered for the interracial kiss.

a hippie who worked many hours rewriting scripts, to make sure of the writing standard was high, the concept was faithful and characters were written right

Show me a man who attributes the success of another man to being ‘lucky’ and I’ll show you a loser.

This article almost makes me wish there was more 70s Roddenberry to examine. Trek fans who loudly proclaim the sanctity of Gene’s Vision are the ones who need to read these articles the most.

So much of what we attribute to GR simply wouldn’t have happened without people like Gene Coon, Bob Justman, Dorothy Fontana, Rick Berman, Michael Piller, Ira Stephen Behr, or Jeri Taylor.

One reason why Trek was his only hit: like Disney, Gene knew who to hire.

it wasn’t his only “hit”. The guy tried to make a buck. WTF? A Rock Hudson, Angie Dickinson, Telly Savalas movie was a bad idea? It wasn’t his script he just produced it. Ignorant

What other project did GR ever work on that became a decade-spanning cultural standard?

I’m not blaming GR for making a living. I’m pointing out how the 70s’ easing of content restrictions did nothing to improve his work.

It’s great that he got to work with that talent. But it’s still a tawdry project.

Moeskido,

Re: What other project did GR ever work on that became a decade-spanning cultural standard?

I’d say, HAVE GUN, WILL TRAVEL, it got syndication sidelined in legal actions across a few decades by Paley’s shenanigans but I think it still qualifies.

Not to side with anyone on the topic, but simply on the facts, Gene wrote the screenplay adaptation. Any deviations from the book are Roddenberry’s writing.

You forgot Ron Moore…

I left out a lot of people, but I was trying to focus primarily on the supervision level before drilling down to the writing staff.

I said this higher up here, but the two most important, to me, are Nick Meyer and Michael Piller (to a lesser extent Rick Berman).

Meyer took Gene’s concept and transformed it into what we know today. Do you think Trek would have survived without the success of TWOK? Likewise, TNG was crearively languishing, surviving in the ratings only because of it’s name recognition. Piller came in and revamped the show as Gene took more of a back seat due to poor health, creating the blueprint for 90s Trek, leading to emmy nods, franchise-best ratings, and 3 spinoffs.

I can’t argue with any of that.

“Do you think Trek would have survived without the success of TWOK?”

Yes, if only ridicolous fan hate did not obscure, in Paramount’s bosses eyes, financial and artistic success of TMP.

TMP was the reason that control of the movies was taken away from Roddenberry and given to Harve Bennett. Its financial success was largely due to merchandise licensing and overseas markets.

Other than as a sizzle reel for a large staff of designers and production artists, TMP was not an artistic success of any kind.

“TMP was the reason that control of the movies was taken away from Roddenberry and given to Harve Bennett.”

I know this. But the ONLY reason for that was the hate of so called “fans”. Nothing more.

“TMP was not an artistic success of any kind.”

You think so.. But Robert J. Sawyer and many others radically disagrees with you:

http://sfwriter.com/blog/?p=2145

http://reflectionsonfilmandtelevision.blogspot.com/2009/04/cult-movie-review-star-trek-motion.html

https://trekmovie.com/2009/12/07/december-7th-1979-star-trek-the-motion-picture-began-30-years-of-star-trek-movies/

http://futuredude.com/why-the-motion-picture-is-my-favorite-star-trek-film/

http://www.ex-astris-scientia.org/episodes/movies.htm#sti

http://sequart.org/magazine/52927/a-defence-of-star-trek-the-motion-picture/

http://startrekspace.blogspot.com/2010/09/star-trek-motion-picture.html

http://ew.com/article/2016/04/29/star-trek-motion-picture-geekly/

http://screencrush.com/star-trek-the-motion-picture-defense/

http://thenewbev.com/blog/2017/06/star-trek-the-motion-picture-2/

TMP was not a big financial success. Why do you think they slashed the budget for the sequel, from 35M to 11M?

TMP made $100 Million more than it’s admittedly outlandish budget.

Simple (Box Office) Statistics:

• “Star Trek: First Contact”– $146 million.

• “Star Trek: The Motion Picture”–$139 million.

• “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home”–$133 million.

• “Star Trek Generations”–$120 million.

• “Star Trek: Insurrection”–$118 million.

• “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan”–$97 million.

• “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country”–$96.9 million.

• “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock”–$87 million.

• “Star Trek Nemesis”–$67 million.

• “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier”–$63 million.

After adjusting their takings for inflation, we have:

• “Star Trek: The Motion Picture”– $398 million US dollars.

• “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home”– $257 million.

• “Star Trek: First Contact”– $244 million.

• “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan”– $237 million.

• “Star Trek: Generations”– $206 million.

• “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock”– $186 million.

• “Star Trek: Insurrection”– $180 million.

• “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country”– $165 million.

• “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier”– $127 million.

• “Star Trek: Nemesis”–$83 million.

Numbers Don’t Lie: ST: TMP is simply the best.

That was one source. Here come the second:

http://www.thecaptainkirkpage.com/trekcom.html

The last column is most significant:

Total Worldwide Grosses Adjusted For 2014 Ticket Price Inflation

1. Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) – $568,227,090

2. Star Trek Into Darkness (2013) – $468,531,354

3. Star Trek (2009) – $419,106,085

4. Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) – $322,926,725

5. Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan (1982) – $282,974,814

6. Star Trek: First Contact (1996) – $269,259,567

7. Star Trek: Generations (1994) – $230,210,447

8. Star Trek III: The Search For Spock (1984) – $222,410,580

9. Star Trek: Insurrection (1998) – $195,648,063

10. Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991) – $187,564,209

11. Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) – $146,207,336

12. Star Trek: Nemesis (2002) – $94,423,328

And yet…

“Paramount considered its gross disappointing compared to expectations and marketing. The Motion Picture’s budget of $46 million, including costs incurred during Phase II production, was the largest for any film made within the United States up to that time. David Gerrold estimated before its release that the film would have to gross two to three times its budget to be profitable for Paramount. The studio faulted Roddenberry’s script rewrites and creative direction for the plodding pace and disappointing gross. While the performance of The Motion Picture convinced the studio to back a (cheaper) sequel, Roddenberry was forced out of its creative control.”

This only proves that Paramout’s executives (and Gerrold) have unrealistic expectations at that time. Because neither sequel (or reboot) was more profitable.

Well first, audience was abysmal for TMP, stellar for TWOK.

Second, you’re focusing far too much on flat dollar amounts rather than percentages, which as a business, is what matters.

$139M on a 35M budget looks good at first glance. $97M on 11M might not look a whole lot better– but that’s an 881% return, vs. TMP’s 397%.

ALSO: TMP pulled in 82M domestically, while TWOK earned 78M. Back then, domestic gross is where the bulk of the money came from, because the cut of foreign box office in the 70s/early 80s was miniscule (percentages have since been re-negotiated several times during the intervening 35+ years).

So domestically we see a 709% return for TWOK, vs TMP’s 234% return.

With all of this considered, any reasonable person would understand why Paramount considered TWOK a bigger financial success.

“Well first, audience was abysmal for TMP, stellar for TWOK.”

Please, don’t mistake audience with haters and hardcore TOS fanboys. Audience went to the cinema. Haters were (and are) vocal (too vocal) minority.

“So domestically we see a 709% return for TWOK, vs TMP’s 234% return.

With all of this considered, any reasonable person would understand why Paramount considered TWOK a bigger financial success.”

First – domestically? The world does not end at United States.

Second – you can’t deny that TMP made twice more money than overrated B-movie named TWOK.

“First – domestically? The world does not end at United States”

Nice cherry pick. I’ll repeat: “Back then, domestic gross is where the bulk of the money came from, because the cut of foreign box office in the 70s/early 80s was miniscule.”

Key word, expectations. There wasn’t anything wrong with the box office, it’s just that Robert Wise gave them 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Paramount wanted Star Wars….

Nothing you’ve said convinces me. Nothing I’ve said convinces you. Let’s let it go, now. Besides, I think history sort of speaks for itself…

Reasonable :)

LLAP _\//

Did you have an industrial accident and lose a finger?

_\//

Oooh I see, the site cuts off the first slash! Funky HTML…

No, I just Yridian.

(Seriously: small typo.)

In fairness, it was the first live-action Trek in over ten years. People were hungry. Heck, wanting Trek is what makes me keep going, no matter the quality.

TMP was one of those 70’s “slow moving pictures” that began with 2001 and ended with Star Wars, but there were some holdovers afterward- Close Encounters, TMP.

He surrounded himself with people who made him look good. Too bad a certain politician (who claimed he could) lacks that skill. And it is a skill– one Gene had in abundance.

Agreed on both counts.

SO much of what we love in TOS was the work of Gene Coon, Dorothy Fontana, John D. F. Black, Bob Justman, and Leonard Nimoy. Roddenberry tried to propagate the “lone visionary” model, but really, it takes a village to make a Star Trek.

‘These Are The voyages’ makes clear that (to the chagrin of most of the writers) that Roddenberry rewrote most of the 1st season episodes to fit his – and our – vision of Star Trek and, frankly, to be better stories. Coon and the others made their own contributions but 95% of TOS was due to Roddenberry. As I’ve stated before: GR created the basic framework of the show, hired all the folks you listed above, supervised the ‘look’ of the show including the design of the Enterprise, and had a very large hand in it’s casting. Gene Coon had a hand in none of that. He contributed humor, Klingons and ‘The Prime directive’ (which was shamelessly ignored then and now). And he gave us ‘Spock’s Brain’.

If you want to talk bad episodes, Roddenberry gave us “The Omega Glory.” :-) Gene Coon gave us “The Devil in the Dark,” and I can’t think of ANY Roddenberry-penned episodes that are as good as that one.

Careful, Anthony, there’s a part of the left ball you didn’t wash!

These Are the Voyages is riddled with factual errors and astounding leaps of logic, like that TOS was a ratings hit in first run. There’s actually a site by Michael Kmet based on fact checking those books with documents from the UCLA archives. I wouldn’t take them as gospel. That being said, I think both Genes gave a lot to Trek and neither one should be used to diminish the other.

I think gene had the overall concept that we love. But I doubt we’d have loved it without the work of those writers, who were able to take his ideas and turn them into something great.

But neither could have created Star Trek (what it is) without the other.

I’ll equate this to an old Stan Lee quote that I both agree and disagree with: when discussing who created Spider-Man he was told by the belligerent interviewer that, (and I’m paraphrasing) “You can’t say that you alone created Spider-Man because without Steve Ditko’s visuals it would not have been successful,” and Stan responded, (and again, paraphrasing) “then fine, then it would have been something unsuccessful that I alone created.”

Which is to say that the IDEA of Spider-Man/Star Trek was certainly the sole creation of Stan Lee/Gene Roddenberry, but that without the work of Steve Ditko/Trek Writers it would not have been what it became, and would not have been successful.

Without Roddenberry, there wouldn’t have been any property Star Trek to begin with. Why all the talk of fans doing too much complaining when it’s about what other people are doing to Star Trek (Discovery), yet it’s OK to complain about Roddenberry? I mean, he only created possibly the most successful property of all time (yeah, I’m including Star Wars — hundreds of hours of TV produces lots of cash — and that’s just money– would a space shuttle ever be named “Millienium Falcon?”. People do that ever day. The guy wasn’t perfect, but you would think he’d get some respect here. We’re not talking about his personal life. Read “Return to Tommorow” about TMP, you’ll find out Roddenberry pretty much saved Captain Kirk from being killed off in TMP — that would have stopped the whole thing before it started.

Great stars in this but I’m more and more convinced that Gene lucked-out creating Star Trek.

Wow. Hmmm. How did I get the hardcover of this book and read it when I was probably something like 14 years old? And mostly forget it? I probably saw it in a used bookstore and knew it was Trek related. Ahh… the early 1980s….

I will have to read this whole article later. My brain already hurts.

Nicely written actually. There is a lot of tale t in that film.

I wish I could remember more how I felt reading the book beyond maybe that it was confusing and slightly sick.

Another pathetic hit-job on Roddenberry by a nerd who doesn’t understand the duality of human nature.

Please explain that duality.

Really? Have you never seen ‘The Enemy Within’?

Boy that’s awfully loose definition of “hit job” you have there, and to derisively label the writer a nerd? Pot, kettle.

I recorded PMAIAR but haven’t watched it yet. I’m going to pass on reading your review here because the opening strikes me as quite dismissive. And you know what? Quentin Tarantino praises PMAIAR as a truly great film. You can say what you will about Quentin Tarantino’s own movies, but the guy is one of the most knowledgeable cinema buffs on the planet, and if he says PMAIAR is legit, then I bet PMAIAR has at least some kind of mojo and integrity beyond the grasp of the comic-con crowd or those Trekkies who fall to pieces because *GASP* the upcoming ‘Star Trek Discovery’ has broken visual continuity with the old Star Trek pilot with Jeffrey Hunter.

I caught this movie on TV not long ago. It’s pretty bad. One of those movies that doesn’t seem to know what it is, shifting wildly from teen dramedy to murder mystery to bonkers satire, and none of it really works. Well, Angie Dickinson is always a plus, ahem, but not much else.

I hate to say it, but reading a certain part of this article only makes me wonder who, exactly attemped to rape (or actually raped?) Grace Lee Whitney.

Along with Doohan and Campbell, another Trek crossover you may have missed, (or maybe I missed it in your review) is Gene once again using Barton Larue as the voice of the newscaster who speaks about the murders being investigated. (I think Doohan is standing in front of a TV during one of those scenes) He was the voice of the Guardian of Forever and was an announcer voice three times I can think of on the old show. He was the voice of the announcer in “Bread and Circuses”, “Patterns of Force”, and the voice of the creature in “Savage Curtain”.

I caught this movie late one night on TCM and couldn’t stop watching it. It was so trippy, so wild,….and it was the next chapter in Gene’s career. I couldn’t stop watching it. And it had a nice soundtrack by Lalo Schifrin.

The things they did in this movie would have been the trial of the decade in real life.

Roddenberry struck lucky with Star Trek but, from reading innumerable behind the scenes books, the one thing they nearly all touch on to a greater or lesser extent is just what a perv this guy truly was. And that’s not me being nasty or casually throwing around insults, it’s mentioned over and over again.

About Roddenberry wanting thing to play straight: It had a major impact on ST: TMP. Leonard Nimoy had an idea for a joke at the end of the movie. In the last scene where Scotty tells him they can take him back to Vulcan, Spock answers ‘My task on Vulcan is completed’m but that’s NOT want Nimoy wanted to say.

In a take, Spock answers back to the engineer ‘My presence on the Enterprise is required if Dr. McCoy is to remain onboard’. Roddenberry thought the joke was inappropriate in light of the seriousness of the events surrounding V’Ger and had a word with Robert Wise. Nimoy dropped his joke and the scene was filmed as it appears in the movie.

If the Nimoy had played in the movie as Nimoy’s instincts told him it should play, it would have tied with the ‘feel’ of TOS in a much stronger way. The humour at end was part of what made it human and part of what separated Trek from the rest.

Roddenberry is a perfect example of how drugs and the Hollywood culture and social circuit can take a normal man with a healthy sex drive and twist him into an unrestrained utopian-preaching pervert. TOS was “liberal’ in the Jack Kennedy manly American way, and you can see Roddenberry’s (AND his works) decline from there as he drifted further left and further debauched.

I’ll never understand why internet guys in their basements who don’t resemble the “manly ideal” at all defend manliness in entertainment so vigorously. It’s that same ideal that shoved you into the basement in the first place. Give it a rest, basement bro. You’re only fostering your own suffering.

Anyone using the moniker “manly trekker” clearly has problems. Not really sure how your reply relates to the post. Perhaps your basement has been filling up with some dangerous fumes affecting your brain. Might want to open a window.

I really enjoyed this piece, but I have to quibble with this claim: “This brought him [Gene Coon] to blows with Roddenberry who wanted the series played straight. Though he still contributed storylines well into the third season, Coon was dropped from his production duties because of this rift.”

Explanations for Coon’s departure are pretty varied, depending on the source (take your pick on the reason – his pending divorce, Shatner and Nimoy’s behavior, physical exhaustion, amphetamine use, the cited argument with Roddenberry about humor, he wanted to write a movie, etc.). However, just about every source I’ve consulted is in agreement on one thing – whatever the reason, Coon left on his own volition, he wasn’t forced out.

According to Inside Star Trek (p.402), one of the conditions of Coon being let out of his contract was that he would contribute story premises for season three if the show was renewed (it was, and he did, as you point out). That suggests to me that Roddenberry wanted him to go on contributing. And, if his comedic voice wasn’t liked, why did Roddenberry continue to use Coon to rewrite “A Piece of The Action,” pushing it into more comedic territory, AFTER Coon left as the show’s producer?

This movie was recommended to me years ago, and it’s still on my to-watch list, but I never knew that it was written by GR until now. I’m going to move it up my list.

The only reason there was more violence relating to sexy women in late 60s and early 70s movies was because the censorship of films had just recently disappeared. In 1967, Hollywood removed the old restrictive codes so they could compete with the increasingly successful independent films. The increase had nothing to do with any kind of “feminism” and whatever specific label you want to add to it. College professors might approve of these ideas, but they have no basis in reality which is usually controlled by cold, hard cash.

Hollywood added more violence, sex and naked women in movies because it turns out that audiences like violence, sex and naked women in movies. The same engine that drives Game of Thrones. It’s also quite likely that Hollywood added more discussion of “feminism” into their articles as a way of sort of offsetting what they were doing in movies. That would actually be a worthwhile investigation. Basically, we’ll kill of a bunch of naked women in movies here and write about how horrible it is over there. Both will sell. Get that Time magazine cover ready. After all, the same companies that produce the movies also own the magazines.

Just discovered this series of reviews and am looking forward to reading them all (and the comments). Has any thought been given to reviewing “The Lieutenant”, the Roddenberry series that preceded TOS? It’s available on DVD, stars Gary Lockwood (and guest stars just about everyone who ever appeared on Trek), and was Roddenberry’s first series attempt to deal with contemporary issues.