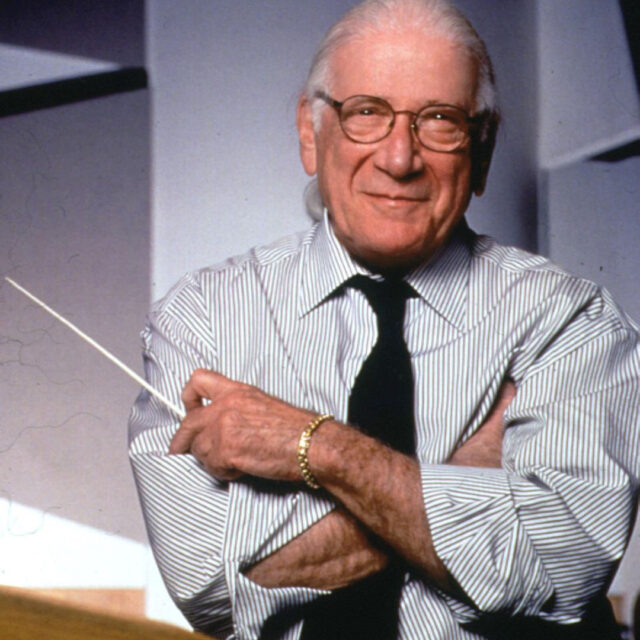

A new two-volume biography is chronicling the life and work of legendary composer Jerry Goldsmith, who played a key part in defining the musical voice of Star Trek. Goldsmith composed the music on five Star Trek feature films, as well as the theme to Star Trek: The Next Generation (repurposed from Star Trek: The Motion Picture) and Star Trek: Voyager. His decades-spanning career included nominations for 18 Academy Awards (including for Star Trek: The Motion Picture), and he won five Emmy Awards (including one for Voyager).

The Jerry Goldsmith Companion

Creature Features Publishing is now fundraising on Kickstarter for The Jerry Goldsmith Companion, an illustrated two-volume biography of Goldsmith. The book is written by TrekMovie contributor Jeff Bond, author of The Music of Star Trek, numerous Star Trek CD liner notes, and (with coauthor Gene Kozicki) Star Trek: The Motion Picture—Inside the Art & Visual Effects.

The following Kickstarter video offers an overview of The Jerry Goldsmith Companion:

The Kickstarter has already exceeded its goal, but is still running for three more weeks. By backing the project, you can reserve your own digital, softcover, or hardcover copy.

Exclusive excerpt on scoring Star Trek: The Motion Picture

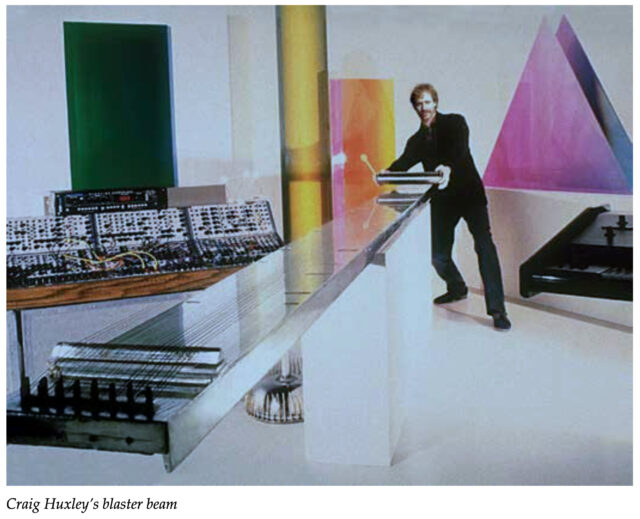

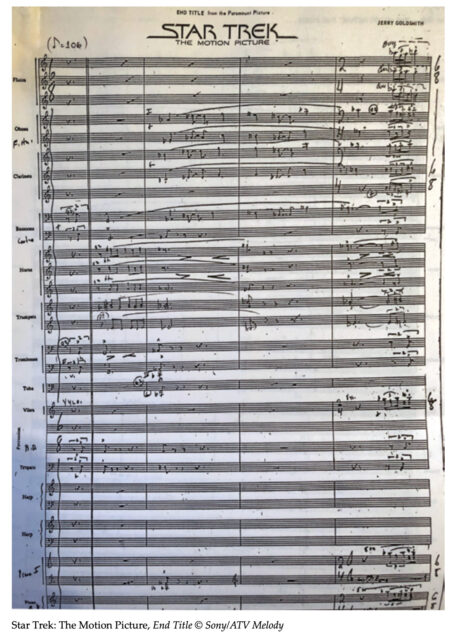

TrekMovie is proud to present an exclusive excerpt from The Jerry Goldsmith Companion about Goldsmith’s Oscar-nominated score to Star Trek: The Motion Picture, including a couple of exclusive images featured in the book. The following excerpt is from volume 2, chapter 5, “The Human Adventure,” covering Goldsmith’s work in 1979, most of which was focused on Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

######################

Jerry Goldsmith watched all of the film’s live-action footage in May while he was at work on Paramount’s Players. “At that time, there were no special effects at all,” he told interviewer Preston Neal Jones. “I was to start the picture officially August 1. I also saw a few tests that Doug [Trumbull] had been doing, and they looked to be remarkable. They were tests for the cloud and for some of the very beginning units of Spock arriving at the Enterprise on his space shuttle, and that’s about it. There was not much more, just a few shots of the Enterprise in drydock.”

Goldsmith was already planning an elaborate score for a large orchestra that would include at least some electronics, a battery of exotic percussion, and a pipe organ. There was only one studio in Hollywood with a soundstage that had a built-in organ: 20th Century Fox. Goldsmith’s relationship with the studio and with Lionel Newman, then nearing his final years as head of music, was still good. But scoring at Fox came with the usual price of Lionel conducting Goldsmith’s music. “Lionel gave him the stage,” Goldsmith’s music editor Ken Hall, himself a fixture at Fox, said in 2000. “That was the game. He gave him the stage and Jerry said, ‘Lionel, would you like to conduct?’ Lionel was conducting for John [Williams at the time], and it was very prestigious—and there’s nothing wrong with that. But that was part of what was going on. Otherwise, why wouldn’t Jerry want to conduct his own?”

Scoring at Fox meant a forced marriage of Fox and Paramount music personnel, with Paramount’s head of music Hunter Murtaugh in the booth, on foreign ground, inside Lionel Newman’s realm, under what would soon become a pressure cooker situation. CBS Records would be putting out the soundtrack album and paying for the recording sessions—an unheard-of situation now.

Bruce Botnick, a recording engineer who had worked with everyone from The Doors to The Rolling Stones, had been assigned to oversee the recording of the score for the album. Botnick explained in 2000 that the idea of the record company paying for the score recording made abundant sense at the time. “At the time that we did this, the record business was outperforming broadcast and film, making more money than anybody. We had money to burn then. Columbia Records used to single-handedly finance musicals on Broadway. So, to them it was the same business model. It was considered pop, actually, because this Star Trek was a popular medium.”

Botnick had an innovation in mind for the project—recording the score digitally, which involved using equipment on loan from Sony. CBS happily agreed, intuiting that the high-tech innovation would be a promotional selling point. “In fact, when we did put out a single, it notated the single timing as minutes seconds and frames on it and Billboard [magazine] saw that and thought that was very cool.”

The project introduced Botnick and Goldsmith for what would become a professional relationship and friendship that would last for the rest of the composer’s life. And Goldsmith’s well-established interest in synthesizers and electronic manipulation of his music made him very open to and enthusiastic about the new digital tool. “I just found him very interesting,” Botnick said in 2000, “immediately, intellectually, and, of course, musically. He was describing what he was wanting to do, and trying to figure out how I fit into the whole thing. And a few of us here were gear-sluts, and he was one as well. And so, he got very intrigued by the idea of recording digitally. He loved that—the fact that we were constantly trying new things to try and advance it. So, he got a better-sounding score on the screen.”

Goldsmith was wrapping his mind around just what the Star Trek score would be—and what it wouldn’t be. Exploring that soon led to the recruitment of a couple of venerable names from the TV series, who also happened to be longtime friends and associates of the composer’s. Star Trek came with certain well-branded associations and expectations, and one was Alexander Courage’s theme music and his fanfare for the Enterprise.

Goldsmith was already dealing with the expectations created by the script, which made specific reference to musical themes and extended musical passages. “The script itself already called for a ‘V’Ger theme,’ and others were discussed by Jerry and me,” Robert Wise told Preston Neal Jones in 1979. Goldsmith needed a theme for Ilia (Persis Khambatta), an alien female involved in a subdued romantic relationship with Stephen Collins’ Will Decker. Ilia becomes an increasingly pivotal part of the plot when she is seemingly killed by V’ger and replaced with a replica designed to interact with the Enterprise crew. The Ilia probe eventually inspires Decker to “merge” with her and V’ger to create a new life form at the end of the story.

Goldsmith began to toy with a theme for V’ger inspired somewhat by the sound of Ralph Vaughan Williams and his Sinfonia Antartica, and the approach rapidly led to a romantic theme for Ilia that worked its way into some of Goldsmith’s earliest cues. “I never really saw anything about V’Ger until the last two weeks,” Goldsmith told Jones. “It was very difficult because there was nothing really there, nothing to explain what V’Ger was about, and there was a tremendous amount of music needed for those scenes. They were guessing how long some of these shots were going to last on screen, but I just didn’t write anything for an effects shot.”

Botnick’s idea to record the score digitally almost caused its own shutdown of the process. “I think the discussion was basically that, by me bringing the equipment in, that I wouldn’t interfere with the progress of the recording, because it was totally unknown,” Botnick said in 2000. “Nobody knew anything about digital, what it could do or what it couldn’t do—so much to the point that a couple of people in the orchestra rebelled against us recording digitally. They thought we were going to replace the orchestra—that it was a synthesizer (it wasn’t; it was just a recorder). And as a consequence, about midway through the recording, I got called into Lionel’s office. And there were two very big burly guys from the union there. And they told me I had to remove my gear. I said, ‘Why?’ They said, ‘Because we’ve had complaints from the orchestra, because they’re gonna take jobs away from the mics.’ At that point, I just called up my people at CBS and told them what was going on. I just decided to remove the gear and continue recording analog two-track with TelDec telecom noise reduction units, and then transfer those over and finish the score, rather than get into a battle that wasn’t worth it.”

During the first weeks of work on the score, CBS was often paying for 100-odd players to sit around and do nothing. “I remember sitting for three days for six hours [a day],” violinist David Newman said in 2000. “But I remember that there were more sessions booked. And it might be because they can only cancel a certain amount ahead of time.” Sometimes Goldsmith would take the players through classical concert works when there was nothing to record while he waited for more special-effects footage to come in (Botnick noted that the composer was into Brahms and Mahler at the time). There was enough footage to tackle a few dialogue scenes with Ilia before Goldsmith realized that he would have to take a stab at the early, pivotal sequence of the Enterprise being viewed in its sparkling new incarnation by Kirk and chief engineer Montgomery Scott (James Doohan), and of the starship leaving its drydock and earth orbit to intercept V’ger.

Goldsmith’s approach to an earlier effects shot (one of the few available to him) of a space station “office complex” in Earth orbit, dictated the sound of the two Enterprise sequences. As he had in Alien, Goldsmith wrote music for the space station filled with swirling glissandos for strings and woodwinds, music that created almost an aquatic, nautical feeling, like the underwater music from Cabo Blanco.

Goldsmith wrote a similar but more grandiose orchestral showpiece for the drydock inspection scene. “The first two big scenes I wrote were the Enterprise in drydock and the Enterprise leaving drydock,” Goldsmith told Jones. “But that was incomplete. So I only wrote up to a certain point and then stopped. I didn’t know what was going to go on next. And that didn’t really come off too well.”

In fact, the drydock scoring was disastrous, at least from Robert Wise’s perspective—and it brought scoring to a halt. “All I remember is we had a morning session, we broke for lunch,” Bruce Botnick recalled in 2000. “And I had taken Hunter [Murtagh]’s Porsche to my office, which was just a few blocks away to take care of some stuff. When I came back, the only person here was Hunter, waiting for his car, and the sessions have been cancelled.”

Goldsmith’s early, rejected score for the Enterprise drydock cue quickly became the stuff of legend, unheard by the general public for two decades until the La-La Land Records release of the complete score in 2012. “It seemed very Debussy La Mer-ish,” David Newman recalled. “It seemed more atmospheric without a real theme.” The subdued treatment of Goldsmith’s four-note motif, with its grand, high-flown bridge, conjured up everything from wind-blown sailing ships to (in Robert Wise’s telling) to Conestoga wagons from classic Westerns. “I’m sure they talked incessantly about that—about it being a nautical metaphor,” Newman said.

“The first time Wise heard the drydock sequence, he disagreed with the approach I’d taken, and he was right,” Goldsmith told Preston Neal Jones. “The basic problem was, I didn’t write a theme, as such. I based the music on a four-note motif. I had all the time in the world to write the sequence and I got all involved from the symphonic standpoint. And it was a marvelous piece of music, it really came out terrific as a piece of concert music. But when I saw it put together with the picture, I said, ‘It’s just dying. It just doesn’t work.’”

Goldsmith took a couple of weeks to reappraise his approach. In the nooks and crannies of his original cues involving Decker and Ilia, vestiges of his avant-garde-styled string and brass writing from projects like Logan’s Run, Damnation Alley, and Alien could still be heard. An experimental sound was still very much required for the film’s V’ger sequences, but the heroic, questing feel of Star Trek—music for Kirk, for the Enterprise itself—fit in more with the romantic sweep that Goldsmith had at least wanted to bring to the bookends of Alien.

The film’s opening also required the kind of dynamic power expected of space operas in the wake of Star Wars—and Goldsmith was just coming off Players, with its rousing, rhythmically driven tennis fanfares. Somewhere along the line a structure for what would become the familiar Star Trek theme and its march presentation came into place. “It just seemed that that’s what they really wanted at Paramount,” Goldsmith said of the march. “It was sort of ‘up’ and noble. I had to go somewhere in between the original TV theme and Star Wars. I didn’t want to go [back] to the old theme; another approach that I had was a very romantic sort of soaring space theme, but it didn’t have the drive to it. So, basically I took the original that I wrote and just changed the structure of it, the meter of it—and fortunately it worked very well.”

Part of Goldsmith’s rhythmic inspiration was a pumping motif for cellos that would now open the drydock scene, establishing the busy, mission-oriented feel of Starfleet at the space station as Scotty prepares to take Kirk on a grand tour of the new Enterprise. Beginning in 6/8 time and eventually moving into 3/8 and 3/4 time, the piece takes the shape of a grand waltz by the time Kirk and Scotty’s small travel

pod encircles the starship and docks with the Enterprise, with Goldsmith’s pumping motif pounded out by the entire orchestra. While the feel is quite different, the hint of a waltz ironically echoes Kubrick’s use of The Blue Danube for 2001’s space station docking ballet. Goldsmith retains some elements of his earlier drydock composition, but the result is a far more rousing and iconic composition. “I was still able to pull out sections of the original and put them in with this tune. So it was no picnic. But the disagreement was no big deal and the revisions worked out better for me.”

They worked out just fine for the filmmakers too. Wise was satisfied with the new approach. And speaking in a video essay on the drydock sequence in 2016, Douglas Trumbull said, “Goldsmith cut loose with the most beautiful music cue ever.”

################

Backing The Jerry Goldsmith Companion

The Jerry Goldsmith Companion features more about Goldsmith’s work on Star Trek: The Motion Picture as well as Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, Star Trek: First Contact, Star Trek: Insurrection, Star Trek: Nemesis, and the theme to Star Trek: Voyager. It is expected to be released in November. For more info or to reserve your own copy, visit the Kickstarter page.

You can also find out more by reading the new interview with author Jeff Bond by TrekMovie contributor Neil Shurley in his latest Star Trekking newsletter.

Find more Star Trek merchandise news and reviews.

As a long-time Doors fan, I had no idea that Bruce Botnick was responsible for recording Goldsmith’s TMP score. Fascinating.

Very cool !!!

I’m a long-time Goldsmith fan and music dabbler and this sounds really cool.

Goldsmith’s scores are THE defining pieces of music for me, and have been my whole life, starting with PATTON and then several Charles Bronson films, especially BREAKHEART PASS (I have a feeling that when I am dying and about to check out, the end music from that film is what I’ll be playing, either on speakers or in my head.) Even most of his scores that I don’t own are often still enjoyable, despite an overreliance IMO on electronics in THE REINCARNATION OF PETER PROUD and LOGAN’S RUN.

The one score of his that I have never been entranced by is the one he got the Oscar for, THE OMEN. To me it just sounds like a lesser take on John Barry’s THE LION IN WINTER (I also get a strong Basil P. CONAN THE BARBARIAN vibe from JG’s theme to TOTAL RECALL, though that isn’t true for the rest o the score. If anybody has a desperate burning need to unload their CD copy of Basil’s IRON EAGLE score, I would be seriously interested, especially now that youtube has taken down the full score and I’m having to watch the DVD to hear the Trek-like greatness in its flying scenes.)

I’ve been listening to JG’s Derek Flint scores this week, along with EXTREME PREJUDICE, THE WIND AND THE LION, THE FINAL FRONTIER and the highjacking cue from AIR FORCE ONE. (to show I’m not monomaniacal, I also listened — repeatedly — to the SF car chase music from THE ROCK, the theme to AIRWOLF and PLAY THAT FUNKY MUSIC WHITE BOY.) Nearly every script I’ve ever written has scenes or whole sequences largely inspired by JG’s music, which is something I cannot say about John Williams, as good as some of his stuff was. EXTREME PREJUDICE has a long unused cue that inspired the whole climactic action in one script, and another unused cue (for the trailer, I think) also drove a whole teleplay.

I’m sorely tempted to buy this new book, but my history with film score related books is not a good one, since I don’t know anything about music at all except what I like (to give you an idea of just how clueless, I was 21 before somebody pointed out that I tap my feet to the melody, not the rhythm.) Goldsmith is so well represented in Preston Jones’ superb RETURN TO TOMORROW that I”m not sure if there’s anything more I ‘need’ to know about TMP’s score, plus I’m trying to back away from being a Trek completist, having managed to avoid recent books by folks who I don’t think were qualified to do TOS and TMP justice.

I’ve always loved the LR score, to the extent that I even think it should be used in the desperately-needed remake. (I once had an extended dinner conversation with William F. Nolan, who felt the same way.)

I can only hope that I’ll have the presence of mind to be playing, or have played, any music in my final moments at all. But for my funeral, it’ll be either Miles Davis’ “All Blues” or Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Riviera Paradise,” both long (but not too long) instrumental pieces that just seem to sum up without words my feelings about the somber, yet still hopeful, experience we call life.

The three J’s of the music industry are all legends (Jerry Goldsmith, John Williams and James Horner). Also do not forget the fact that Goldsmith’s son Joel was also a successful composer and did the music for the Stargate series.

When you said “the three J’s” I thought the 3rd would be John Barry.

Make it the four J’s.

Interesting stuff. Many CD’s had really good notes in the notebook sleeves. I always enjoyed that when they came with those. And disappointed when there was next to nothing. One thing I did enjoy was I recall an interview with Goldsmith when he said he “got a lot of mileage out of that one” when asked about the TMP theme.

The moST fantastic score ever created…