Star Trek: Picard – The Last Best Hope

Written by Una McCormack

“How many people do you think died after we left?’

He shook his head. “We don’t know that happened, Jocan. We can’t berate ourselves over hypotheticals –”

“These are not hypotheticals!” She reached into her pocket and threw a tricorder onto the table. “Look! Watch what’s on there!”

Raffi picked it up. She ran it around in her hands, turned it on, and set it to play. A small flickering image, recognizable as the ramshackle square of the main settlement on Nimbus, appeared. She could make out figures – nearly fifty people, hands on their heads. Then the shooting started. It didn’t stop until everyone was lying on the ground, dead.

“Mon dieu,” whispered Picard.

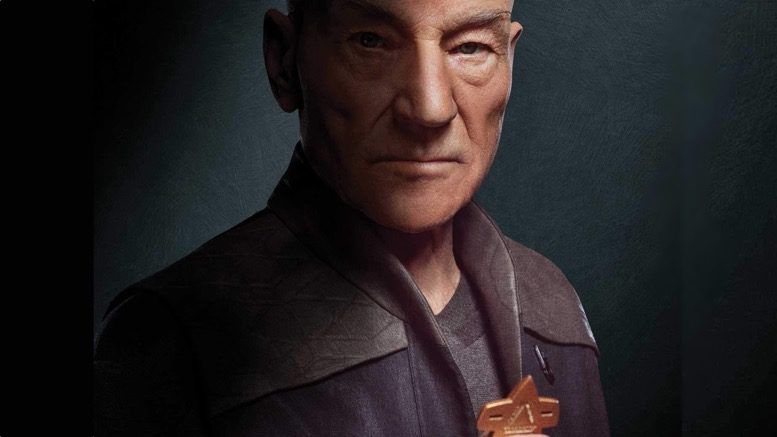

With the debut of the new CBS All Access series Star Trek: Picard, many fans who had disliked the direction taken by both the J.J. Abrams Trek movies of 2009-2016 and Star Trek: Discovery, hoped that the return of one of Starfleet’s most famous captains would herald a return to what they considered to be the best of Trek. As of this writing, with five episodes of Picard under our belts and five to go in the first season, it’s fair to say that while many fans have been delighted by Jean- Luc’s reappearance on our screens, there have also been a number of huge questions and concerns raised about the fictional world our characters now inhabit, about its moral character, and about its depiction of Jean-Luc Picard himself.

Fans who care about these types of questions would be well advised to pick up and read the brand-new tie-in novel by Una McCormack, Star Trek: Picard – The Last Best Hope. McCormack addresses them all, and in a way that feels like well-prepared back story rather than an author scrambling to fill plot holes.

Before diving into spoiler territory, let me say that Una McCormack is probably my favorite Trek novelist writing today, and she is an excellent choice for this project. In her previous Trek novels, like 2009’s The Never-Ending Sacrifice, and 2017’s Enigma Tales, she has shown a deftness in handling the moving of larger, societal forces on a cultural scale. And in 2019’s Discovery tie-in novel The Way to the Stars, she has shown the ability to tell deeply-personal stories laser-focused on the characters themselves. Both of those skills are in ample evidence in The Last Best Hope.

This novel covers the period between the discovery of the impending Romulan supernova and the immediate aftermath of the “rogue synth” attacks on Mars, the four years from 2381-2385. Because viewers of Star Trek: Picard (and Short Treks: “Children of Mars” know how this story is going to end, the narrative has a feeling of inevitability and doom about it, which McCormack manages well, in contrast to the optimism of its central character. We watch Picard doggedly persisting in his impossible mission, maintaining hope and a vision for saving lives, even as wider forces, many of which he has no knowledge of, unfold darkly in such a way that we know a clash must inevitably happen.

It is a novel about how hope and pragmatism play out in a society that is both enlightened and comprised of real beings with real emotions and desires. I think that it binds those concepts together in a way that both makes sense and is resolutely clear-eyed about unchangeable truths about humanity. When I wasn’t reading the book, I was thinking about it, and hoping for my next chance to pick it up again. Like other tie-in novels, it fills in some of the blanks left by the brisk writing of time-constrained television production, but unlike most tie-ins, the blanks filled here feel necessary, consequential, and foundational to understanding the show itself. In a word, The Last Best Hope makes the experience of watching Star Trek: Picard richer. I highly recommend it to any Trek fan watching the show.

If you’re not watching Star Trek: Picard, does the book stand alone as its own story? Yes, but the book leaves Picard broken in ways that the show starts to put back together. If you love the character of Jean-Luc Picard, this book takes him to a place you likely don’t want to see him end up in. You will want the show to help him find his way back.

Now for a few spoilers. Don’t read further unless you’ve seen the first five episodes of Star Trek: Picard and read this novel, unless you don’t mind hints about what took place.

McCormack carefully draws the progress of the Romulan resettlement mission from its “impossible dream” beginning to its crushing-defeat end. In the process, she weaves together the politics of the Federation, the economic concerns of border worlds, the difficulty of working with a xenophobic and secretive society like the Romulan Star Empire, and the stunningly difficult logistics inherent in a rescue mission like this.

To tackle the last concern first, in PIC: “Remembrance” and elsewhere, it has been mentioned that about nine hundred million Romulans needed to be resettled in advance of the Romulan supernova event.

Logistically, how would such a thing be possible? How much time would be necessary? How many ships? Where would they all go? Just to break it down a little, assume a fleet of thirty starships, each holding 800 passengers, and able to transport groups of 20 from the surface of a planet in batches, with three minutes to gather each group, beam them up, and get them off the transporter pad and out of the room to make ready for the next group. Okay, so it would only take about two hours, if all went well, to fill the ship’s complement. Then you warp out for a week-long journey to the place you’re settling the refugees, beam them all down, then come back. How long would it take those thirty ships to evacuate a planetary population of a modest 6 million people? 3,500 days, give or take: about 9 ½ years. For one planet, with thirty ships. Let’s say you had 300 ships, how long would it take to evacuate 900,000,000 Romulans? By my calculations, roughly 144 years. This is a staggering undertaking!

I had the same thoughts while watching the first episode of the CW’s Arrowverse crossover event, “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” where Oliver Queen, the Green Arrow, stands alone, fighting off shadowy attackers, protecting the retreat of refugee ships escaping through a portal. He stands his ground for about an extra minute or so, and in so doing saved a million extra people. But there was only one portal, and a million people is a lot of people! So if one ship with 100 people on it takes 5 seconds to go through the portal, the minute that Queen stood his ground could only have saved 2000 extra people. Put another way, if it takes five seconds for a ship to go through the portal, to save one million people in one minute, each ship would have to be carrying 50,000 refugees. A ship carrying 50,000 refugees would have to be the size of an Imperial Star Destroyer (crew and passengers: 46,785 according to Wookieepedia). You get the point. It takes time to move people, and moving a lot of people takes a lot of time.

McCormack’s book takes this staggering logistical challenge to heart. How many ships would it take? How would you build those ships? Where would you get the labor force to build those ships? If those people (and synths) are building ships, they are not doing other things, presumably things they were doing before, and liked doing. How would they feel about being diverted from their life’s work to this mission? McCormack tackles these questions with intelligence and heart.

She depicts Raffi’s heart-wrenching personal sacrifices alongside Picard’s benevolent obliviousness in ways that show both characters as believably noble and flawed. She takes us deeply into Romulan paranoia and secrecy (though thankfully, neither Narissa nor Narek make an appearance), into inter-Starfleet politics, and into Federation politics and portrays the actions and motivations of everyone involved clearly enough that you can see why everyone believes that what they are doing is the right decision to make, given what they know or believe. McCormack humanizes Captain Kirsten Clancy, who appears in PIC: “Maps and Legends” as the hard-nosed Starfleet Commander-in-Chief who swears at Picard in frustration.

Most movingly, we get to see how Romulan warrior-nun Zani functions both as Picard’s kindred spirit and the guardian of his sense of hope. And we see how both the exigencies of a difficult mission, Federation politics, and the challenges of Romulan culture all serve to push Picard’s hope to the breaking point.

But won’t we have progressed beyond petty local politics and parochial economic concerns in a post-scarcity future? McCormack argues that even in a utopian Federation society, the distribution of goods and production will never be completely even. Worlds that are brand-new to the Federation, or further out from the center of the UFP, will be in the process of transforming to a post-scarcity society, but will not arrive instantaneously. It is not a betrayal of Gene Roddenberry’s vision to posit that distant newcomers to the Federation might not yet have societies as enlightened as those of Earth, Vulcan, Tellar, and Andor. Nor that keeping those planets in the Federation might be a noble goal that might require some less than ideal decisions. As Picard said in “Absolute Candor,” it is easy to allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good.

Truthfully, the idea of the Federation as a homogeneously idyllic, utopian society has always been more a product of Gene Roddenberry’s offscreen interviews than of onscreen canon. Racial bigotry towards Romulans makes its first appearance right alongside their debut in TOS: “Balance of Terror.” The non-existence of money in the Federation is mentioned at times, but is contradicted at other times, from the first season TOS episode, “Mudd’s Women” to McCoy’s offering money to charter a space flight in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. While Picard tells Lily Sloane that humanity has evolved past emotions like a desire for revenge in Star Trek: First Contact, she rightly calls that assertion “bullshit,” and calls Picard to listen to the better angels of his nature.

Like I said, fans may not agree with these arguments, and may not like where they lead, but McCormack treats them head-on, with intelligence and humanity. And while other tie-in novels sometimes feel like the author is using the novel to address inconsistencies between the parent show and canon, The Last Best Hope feels like backstory that the production crew carefully worked out for the show but didn’t have the time to include. Reading it makes a good show even richer and more enjoyable.

Some nitpicks do stand out. For one thing, the explanation for the need for synth labor is hard to swallow. I find it inconceivable that a starship would have a significant number – or any number! – of parts that have to be hand-made. And that is the entire argument for the need for synths! Every 21st-Century person has seen video of an automobile assembly plant, with non-humanoid robots doing assembly tasks. If making these parts requires hands, and only hands will do, why not build non-humanoid robots that just have humanoid hands? Why give them heads, and faces, and legs?

My only major concern about the novel is a matter of personal preference: I don’t find the expansion of coarse language in Star Trek to be a step in a positive direction for the franchise. I don’t believe that the incorporation of frequent f-bombs and s-bombs makes the show more relatable, believable, or richer, and aside from the pilot, which was set to be released for free on YouTube after its airing on All Access, Star Trek: Picard has included one or two bleep-able words in each episode. I know that the producers feel that they need to give people their money’s worth for subscribing to the streaming service, but I don’t find that profanity adds value to the show. And in that vein, all characters surrounding Picard swear a whole lot in The Last Best Hope, though not the man himself. The book would have been at least as good without that, and in my mind, better. But I understand that’s a personal opinion that you might not share. What I believe you will share is my conviction that this is an excellent tie-in novel that deepens your appreciation for the show it is based on.

DISCLAIMER: We may link to products to buy on Amazon in our articles, these links are customized affiliate links that support TrekMovie by earning a small commission when you purchase through the links.

I’m not against swearing per se, but the swearing in Picard is unimaginative: the swear words are today’s, which pulls me out of the fictional futuristic world of Trek. They should use a different way of swearing/insulting, like McCoy with “you green blooded…” or imported Klingon swear words “P’tak” or other.

Replace f* with Ql’YaH and s* with Baka (japanese for idiot; just like in TNG when Captain Picard once said merde!), and we’d be fine, without taking away from the meaning of the scene.

It is the same with the clothes. The clothes look too contemporary, and except for the Starfleet uniforms, they don’t look like from a different time. The clearest example is when you look at a Picard photo shot between takes, the actors look just like the crew!

The story is fine. Shame the world building is not as imaginative as it used to be in Star Trek of old. Maybe they have too much money to play with.

I get that certain words bother certain people, but to suggest that these words would have withered up and died is silly, especially since people have been using the dread “F” word and its counterparts lot longer than you give them credit for. For its use to continue into the 25th century is entirely possible.

Was there this kind of uproar when Kirk and McCoy took to using blasphemy in the feature films of the 1980s? That stands out more to me than Rios and Admiral Clancy using an f-bomb, because (to the best of my knowledge) none of these characters believe in the Christian God or his son Jesus Christ, yet Kirk and Bones invoke their names some 2300 years after the birth of Christ.

My point? I’m sorry if the big one, the queen-mother of dirty words, the F-dash-dash-dash word offends you, but please don’t suggest it would have ever gone anywhere, because that theory’s just a rotting pile of forshak.

Where did you get that impression from? It doesn’t offend me at all. I also never said that the swear words would disappear (it could, it could not, that’s not my point). It just takes me out of the fictional Trek world to today. Just like the clothes. It’s unimaginative. It’s like someone on NCIS swearing with a Shakespearian “varlot” or “flap dragon”. They can use f*k all they like in the right Trek context, like for example, time travelling or holodecking to the 21st century and trying to fit in.

The point of Trek is to imagine the future, not recreate the present.

PS: just to clarify, I’m not vehement about anything in the choices of the production, it was just a minor observation. I don’t take the fictional world to be more than it is. I like all of Star Trek, warts and all, whether I agree or disagree with various choices, and watch all of all the series. They all bring me something different and worthwhile. And I’m happy to acknowledge that there are things I may not like in Trek that you may like, and vice versa. No problems with me. :)

My apologies for misunderstanding (and for being snarky earlier)… not the way one should behave when trying to have a mature conversation. I’ll strive to be better.

To me, and I’m sure I’m in the minority, but for me it makes Trek much more human. Kirk can call the Klingons “bastards” but other swear words would have just disappeared? That never made sense to me. There are insults in the Romulan language, the Klingon language and others as we’ve found out in previous Trek shows so why would they go away in the human language? Recognizing it is just something that most tv trek couldn’t do.

I agree with this. Heck McCoy even has a dirty mouth even in the first movie!

If Picard is your “last best hope” your pretty much as doomed as the Enterprise-D facing a 150 year old Bird of Prey or the Starfleet at Wolf 359.

love the new series… im going to read this

Thanks Dénes for this.

I admit that I’m still working my way through the back end of this novel even though I’ve had it since its day of release.

It’s incredibly sad, such that I find that I’m reading it in small bites – due to the emotional impact – the writing is Trek-lit at its best.

I’m viewing this story as a true classic tragedy in the Shakespearean sense. What better character to embody a true tragedy than Patrick Stewart’s Picard?

Trek audiences may not be comfortable with a classical tragedy’s uncompromising end, or welcome the catharsis, but no one can claim that it’s an invalid artistic choice.

And unlike a classical audience, we have the opportunity in the television series to see Picard, Raffi and the Federation confront their tragic flaws, overcome them and reach for the ideals Trek is anchored in.

I’ll get back with more when I’m finished, but I totally agree that it’s essential reading and that McCormack was a brilliant choice of author for this novel.

I’ve finished, but I confess that I read it in small bites through to the end.

The abandonment of lower status Romulans by both their own leadership and the Federation was heartbreaking, but not because I felt that my concept of the Trek utopia was betrayed.

Like other commentators, I found the failings on all sides credible, and the eventual decision by the Federation Council believable. This was a tragedy of classical proportions, that was rooted in the tragic flaws of the Federation, Starfleet, Picard, and the Romulans themselves.

Definitely one of the best of Trek-lit. A 5 out of 5.

And it still has me wondering if Jurati was compromised from the moment she arrived at Daystrom as a grad student, while providing just enough to make credible her romantic pursuit of Maddox and then refusal to leave Earth after the Mars attack.

Agreed. This is essential reading. I absolutely loved it.

I was watching a VOY episode last night, where 7 needs a new cortical node, and in that ep it’s mentioned even the Borg can’t replicate (or was it repair?) new cortical nodes, so they always had to be replaced.

That made me appreciate a bit more that some parts still have to be handmade, as fancy as replicators are.

Your point is well taken in why did it have to be synths? But…I’m still mostly okay with it. :)

I read “The Last Best Hope” while I was away on vacation last week, which also meant that I didn’t get to watch last week’s Picard episode until last night. I don’t think I can overstate how deeply the novel provides context for the series. There is a sense of inevitability regarding the end of the story, but the backstory is essential reading for anyone who wants to fully understand the direction of the show, and a great read at that. Highly recommended!

I’m sorry to throw in a vaguely negative comment here, but I have to question – why should I have to read a book “to fully understand the direction of the show?” Why can’t the show itself do that? Don’t get me wrong, I’m an avid reader (not necessarily of Trek lit), and fully appreciate a well-written book, but why is it fans are now expected to seek out literature to make what they watch on television ‘whole?’

Danpaine, there’s a longstanding tension in film and television about how much exposition and backstory to include vs let the audience figure it out themselves. Neither is the ‘right’ way.

American entertainment television and film have leaned to showing everything as compared to art films or international visual media, but that’s changing as media goes global.

The writers are excited to be offer a product that doesn’t need to spell everything out.

For many of us, the show is enough, but if knowing the details is something one really wants or needs, the books will be there.

Really enjoying the book so far. I haven’t had time to sit and plow through it like I normally would have but everything I’ve gotten through so far is so good. Trek is really expanding and damn am I loving it.

“Trek is really expanding and damn am I loving it.”

Same! It feels like its the first time in over 15 years the universe is getting bigger again and not just filled with endless back story to things we already know. The show isn’t perfect by a long shot but it does feel like a welcome change and brings excitement again to people sick of prequels (like me).

Yeah, that countdown clock on the Genesis device in the closing act of WOK is all over the place, and a favorite Trek pet peeve. Time stands still while all sorts of stuff is going on, Enterprise does have impluse power, and for the time on the detonator, she would still have been millions of miles away from Reliant when she blew. Oh, well…

I wonder how this continuity (that of the TV series) relates to that of the expanded universe of Star Trek The destruction of the Borg? Typhon Pact?

The continuity of the relaunch novels has ended, at least since 2380.

We have to think of the Destiny trilogy and the Typhon Pact and later novels as being in an alternate timeline.

Seems an interesting book. I find the calculations for saving the Romulans very realistic. Suddenly, the decision of Spock to try to save the Sun makes perfect sens. Strangely, it also points out at how desperate the actions of Picard were before the Tv series. I understand better the resentments of Raffi now. Her current state wasn’t well explained in the serie, in my opinion.